ASEAN's failure to agree a joint communique at its meeting in July reflects a split within the organisation between Chinese and US allied states in the region. Given the context of rising naval armament in the Pacific, the lack of an agreed resolution mechanism for maritime boundary disputes raises the prospect of further incidents relating to oil and gas exploration overshadowed by growing big power rivalry.

Tensions rose in July over unresolved maritime disputes in both the South China Sea and the East China Sea. China is flexing its muscles and appears to have warded off any progress towards agreement on a coordinated and united response to dispute resolution amongst the countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, which met in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in July. For the first time in its history, ASEAN failed to produce a joint communique at the end of its meeting.

This article was published in the August issue of Platts Energy Economist. Platts is a media partner.

(Photo Credit: iStockphoto.com)

The lack of a final communique was attributed to Cambodian resistence to mentioning the unresolved nature of a dispute between the Philippines and China over Scarborough Shoal (known to China as Huayang), part of the Spratly chain of islands in the South China Sea. China, which attended the Phnom Penh meeting as an observer, prefers bilateral negotiations, a position generally seen as allowing it to maximise its financial and economic leverage over individual countries in the region. ASEAN was set up in 1967 by Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Singapore. Brunei joined in 1984, followed by Vietnam in 1995, Laos and Burma in 1997 and Cambodia in 1999.

Incidents proliferate

China also chose the meeting in Phnom Penh as an appropriate moment to send ships into waters disputed with Japan in the East China Sea. The Japanese coastguard reported three Chinese ships entering disputed waters July 11 around what Japan calls the Senkaku Islands and China Diaoyu. The move prompted Tokyo to make a formal complaint to the Chinese Ambassador to Japan and the countries' foreign ministers met in Phnom Penh. Both restated their claims that the islands were and have historically been part of their respective territories.

Japan was forced to lodge a second complaint with Beijing after a Chinese patrol ship neared the islands July 12. The Japanese coastguard said theYuzheng 33001approached the islands and remained in the area, insisting it was "patrolling Chinese waters". The uninhabited outcrops were the scene of an incident in late 2010 when Japan arrested a Chinese trawler that had rammed two of its coastguard vessels. A week long standoff resulted, in which bilateral ties were frozen and Chinese exports of materials vital to high-tech manufacturing were curtailed. Japan eventually released the trawler captain.

South Korea is also involved in maritime boundary issues in the area. Seoul wants to expand its southern continental shelf to include the northern area of the East China Sea, despite disputes with Japan and China. South Korea plans to submit this year an official claim to an extended portion of the continental shelf beyond its Exclusive Economic Zone in the East China Sea. The government claims its right to develop an expanded area because the Korean Peninsula's continental shelf naturally stretches to the Okinawa Trough, said an official.

The Ministry originally planned to summit the document in July, but postponed this to later this year following a protest by Japan. The ministry official declined to disclose further details. "It is our basic stance that our continental shelf stretches to the Okinawa Trough," the Ministry official told a press briefing.

The disputed maritime region is believed to hold significant gas and oil reserves. South Korea explored its block 7 in the disputed area in the 1980s jointly with Japan. However, Japan stopped exploration, saying the block did not hold economically recoverable deposits. Last year, South Korea launched an exploration initiative on block 6. Seoul's energy ministry estimates that two parts of block 6-1 contain 13.8Bcm of gas reserves. Block 6-1 is just north of the Donghae-1 field and has produced 1.38MMcm of gas and 1,000 barrels of crude oil since 2004.

However, the dispute which caused the failure to agree a common stance in Cambodia occurred earlier this year in April and May between China and the Philippines regarding Scarborough Shoal. Both countries posted a number of vessels around the shoal from early April after Chinese naval ships prevented the Philippine coastguard from arresting Chinese fishermen.

Although the incident had de-escalated by July, Philippine President Benigno Aquino said 5 July that Manila was considering asking the US to deploy spy planes over the South China Sea to help surveillance of the disputed waters. This prompted a series of articles in the Chinese press accusing the Philippines of raising tensions over the issue ahead of the ASEAN summit, and in particular of increasing US involvement in the issue.

The Scarborough Shoal skirmish comes amid ongoing conflict between China and Vietnam over offshore oil and gas blocks offered by the China National Offshore Oil Corp. in June, which are close to Vietnam's northern coast and which overlap acreage already awarded by Hanoi to foreign companies. State company Petrovietnam 29 June wrote to international oil companies operating in Vietnam requesting them to respect Vietnam's sovereignty and jurisdiction by not participating in the nine offshore blocks offered by CNOOC.

Vietnam also passed a maritime law 21 June, which clearly places both the disputed Spratly (Nansha) and Paracel (Xisha) islands under Vietnamese sovereignty. The move caused China to summon the Vietnamese ambassador in Beijing in protest. China also announced that it had elevated the administrative status of the islands from a county to prefectural-level district.

Overlapping claims

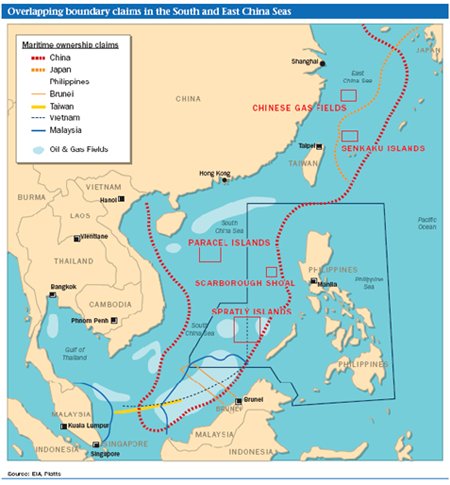

While China, Japan and South Korea are the main actors in the East China Sea, the extent of claims in the South China Sea extends beyond China, Vietnam and the Philippines. China claims virtually all of the South China Sea as its territory, but Indonesia, Brunei and Malaysia all have claims for parts of the region. Most of these are based on the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which allows claims based on both a 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone from land and the extension of countries' subsea continental shelves, a situation which often results in overlapping claims.

Actual and possible oil and gas reserves are a key element of the disputes. According to the US Energy

Information Administration, a lack of drilling in the South China Sea means that hydrocarbon resource estimates for the area are highly uncertain. The EIA quotes Chinese estimates of potential reserves for the Spratly and Paracel islands of 105 billion barrels up to 213 billion barrels, as well as a 1993/94 estimate by the US Geological Survey of discovered and undiscovered resources of 28 billion barrels. The EIA says that some 60-70 percent of the hydrocarbon resources in the region are likely to be gas rather than oil.

East China Sea reserve estimates are similarly uncertain, with Chinese figures generally higher than others, ranging from 70-160 billion barrels for the entire East China Sea, but much less for areas that are actually contested. Chinese estimates for the natural gas resource for the entire area range from 175-210Tcf. China already produces oil and gas from some contested areas, but has broadly stuck to the unofficial median line between its own waters and Japanese waters. Tokyo has expressed concern that Chinese oil and gas developments are tapping fields that extend over its side of the median line.

Arms race

The various maritime boundary disputes, and the lack of an agreed resolution process, have to be seen in the context of what many defence experts view as a regional arms race. The UK Royal United Services Institute says: "A wave of defence acquisitions from Burma to Indonesia has accelerated a regional arms race. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute's Arms Transfers Database, arms deliveries to Southeast Asia nearly doubled from 2005 to 2009 compared to the five preceding years, with weapons deliveries to Malaysia jumping by 722 percent Singapore by 146 percent and Indonesia by 84 percent." Many of these acquisitions are targeted at expanded naval power.

The backdrop to this is China's own increasing ability to project force at sea. China is expected to commission its first aircraft carrier this year, following sea trials that have been underway since 2011. Although limited in capacity and weapons systems, the carrier represents the ability to project power well beyond Taiwan, suggesting the target theatre of operation is the South China Sea.

In addition, according to an annual Pentagon report on China's growing military power, "the PLA air force is transforming into a force capable of offshore offensive and defensive operations". Although expressing doubts about the Chinese carrier's capabilities, RUSI writes: "A more likely scenario is that Beijing could consider deploying the ex-Varyagto intimidate its less well-armed neighbours in the disputed South China Sea."

China's build-up of arms has been accompanied by a change in US military strategy to focus on the Pacific Ocean rather than the Atlantic, raising concerns about big power rivalry in the region. At a speech given in June in Singapore as part of the 11th IISS Asia Security Summit, US Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta clearly outlined US interest in the Pacific region, saying that "by 2020 the [US] Navy will reposture its forces from today's roughly 50/50 percent split between the Pacific and the Atlantic to about a 60/40 split between those oceans. That will include six aircraft carriers in this region, a majority of our cruisers, destroyers, Littoral Combat Ships, and submarines".

ASEAN split

The inability of ASEAN to reach a joint agreement at its meeting in July suggests a split in the organization that reflects this rivalry. Vietnam and the Philippines are US allies, while Cambodia is seen as an ally of China.

According to Tan Seng Chye a senior fellow at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, ASEAN's approach has been that disputes should be resolved peacefully among the claimant states in accordance with international law and UNCLOS, supported by the Declaration of Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea and the Implementing Guidelines of 2011. The breakdown in Phnom Penh suggests this direction may no longer be possible.

Moreover, he argues, the lack of agreement on the South China Sea has meant no final communique on other more important issues facing ASEAN, indicating "ASEAN's lack of cohesion and solidarity in pursuing issues of common interest to ASEAN, unlike in the past".

Chye says: "The new era of emerging big power rivalry in the region involves the US' enhanced engagement in the Asia region and its pivot or re-balancing of its military forces to Asia Pacific as well as China's response to the US strategy to conscribe it." He argues that ASEAN's cohesion is falling foul of US intervention and China's refusal to accept external involvement "or even regional participation in its bilateral disputes".

According to Sabam Siagian, Indonesian Ambassador to Australia, writing in theJakarta Timesin July: "There are, at least, two approaches in viewing the un-ASEAN events in Phnom Penh. The benign approach would explain the failure to produce the traditional final communique at the end of the annual foreign ministers' meeting as a sign of ASEAN's maturity.

"Now, serious differences are not papered over. The second approach views the events in Phnom Penh more realistically and as events that we should heed seriously. Phnom Penh, this view submits, is a preliminary skirmish that juxtaposes China and the US," he wrote.

Siagian noted that Philippino Foreign Minister Albert del Rosario "was indeed blunt--and very un-ASEAN--when he directly accused the Chair, Cambodia's foreign minister Hor Namhong, of 'consistently defending China's interest'.". Siagian continued: "Could it be that the Philippines, ever so receptive and appreciative of US' rhetoric and movements, has become emboldened and decided to discard ASEAN's non-confrontational approach"

If so, the July meeting in Phonm Penh represents a turning point for ASEAN, but not necessarily a positive one. The organisation has traditionally moved forward cautiously, always on the basis of consensus and has often been accused of brushing serious issues under the carpet. The Phonm Penh disagreement suggests that this mode of operation may no longer work.

BY: Platts Energy Economist