July saw the arrival not just of the British rainy season, but the first short-term forecasts from the International Energy Agency and OPEC regarding oil demand and supply for the year ahead, published in their monthly oil reports. The US Energy Information Administration started earlier in January. From here on in, these numbers, despite their uncertainty, play an important role in forming expectations regarding the balance between oil supply and demand, known in market and economic parlance as the "fundamentals".

These fundamentals have a large bearing on price, but by no means an overriding one. There is a huge amount of literature and debate on the role of fundamentals in price formation, but also little doubt that the oil market is subject to a variety of geopolitical, economic, regulatory, social and technological forces that often have a greater impact than that which might be assumed from the apparent balance between supply and demand. Not least amongst these is the fact that about one third of all crude supply is controlled by OPEC.

This article was published in the August issue of Platts Energy Economist. Platts is a media partner.

However, it is clear that the initial forecasts for 2013 jar significantly with the assumptions underlying long-term forecasts. The long-term outlook sees continued strong oil demand from developing economies over the period out to 2030-35, and beyond, based on high GDP growth potential, rises in population, urbanisation and increasing levels of income from a low level, a period of development that is particularly oil intensive.

In particular, growth in oil demand in the non-OECD is expected to outstrip the opposite trend for contraction in the OECD by an order of some magnitude, creating significant supply-side challenges that support a rising oil price over the long term. On this prognosis, the development of high-cost frontier oil is a sound bet, one that is attracting billions of dollars in investment capital.

In addition, the expectation is that OPEC's share of the market will rise as OECD production declines, increasing the insecurity of oil supply in both OECD markets and the major emerging markets such as China and India, providing OPEC with increasing power over pricing. The short-term outlook, by contrast, tells a different story. Reduced demand in the OECD offsets to a greater than expected extent demand growth elsewhere. Combined with strong OECD supply growth--buoyed by years of high oil prices and technological innovation--this means that supply growth is greater than overall demand growth Moreover, the short-term data suggest that non-OECD economic growth is still heavily dependent on the health of the OECD economies, a link which weakens in the context of longer-term outlooks. Furthermore, the Chinese economy--the main engine of demand growth for oil--may be experiencing internally-generated problems that will divert it from its current rapid path of economic expansion. This differs from the view that China will gradually shift from export-orientated growth to develop a more balanced internal growth dynamic of its own.

This variance between short and long-term forecasts raises the question of whether 2013 represents a blip of uncertain duration from the long-term trend, or the start of a new scenario based on less visible but still identifiable developments. As a result, it may be that a major overhaul of existing assumptions regarding the long-term outlook for oil demand is required.

Forecasts for 2013

The EIA's July Short-Term Energy Outlook included some major revisions to expected oil demand and supply in 2012 and 2013. The forecast for oil demand growth was lowered by 240,000b/d for 2012 to 670,000b/d, leaving total consumption at 88.64 million b/d, and, for 2013, by 670,000b/d to 730,000b/d to put total consumption at 89.37 million b/d.

The forecast for non-OPEC supply was put at 52.66 million b/d in 2012 and 53.93 million b/d in 2013, representing year-on-year increases of 750,000b/d and 1.27 million b/d, respectively. For 2012, the balance between non-OPEC supply growth (non-OPEC supply plus OPEC Natural Gas Liquids) and demand growth has shrunk by 60,000b/d--supply growth will exceed demand growth by 340,000b/d, rather than the 400,000b/d estimated in the June STEO.

However, in 2013, that balance has expanded to an excess of 590,000b/d. This is a big jump compared with the June STEO, which put the figure at 240,000b/d. Although total supply depends on OPEC, the EIA's new outlook effectively inverts expectations regarding 2012 and 2013. Next year now looks weaker than this year, rather than the other way around. It implies that OPEC will have to curtail production significantly to maintain prices and that non-OPEC supply will make inroads into OPEC's share of the oil market globally.

OPEC itself makes a similar prognosis: Oil demand will grow by 800,000b/d in contrast to supply growth from non-OPEC and OPEC NGLs combined of 1.2 million b/d. NGLs are light condensates that are not covered by OPEC's production targets, but nonetheless enter the blending pool or displace crude oil products in various industrial applications.

Significantly, the "call on OPEC"--how much crude the cartel needs to produce to balance supply and demand--is estimated to average 29.6 million b/d over the course of 2013. According to a Platts survey of OPEC production, the organisation was producing 31.72 million b/d in June, way above OPEC's own supposed target of 30 million b/d and the expected call on OPEC in 2012 of an average 29.9 million b/d, based on the organisation's own figures.

The IEA's numbers diverge significantly from the forecasts of both the EIA and OPEC. First, the IEA expects demand growth to be greater in 2013, putting the figure at 1 million b/d. Second, it expects growth in non-OPEC supply to be smaller at 700,000b/d. Although it gives the highest figure for growth in OPEC NGLs in 2013 at 300,000b/d, the net effect is to forecast supply growth as exactly in balance with demand growth in both 2012 and 2013.

The IEA's call on OPEC is therefore substantially higher than either the EIA or OPEC for 2013 at 30.50 million b/d, above OPEC's nominal 30 million b/d target, but still well below current production.

Departures from trend

The forecasts overall suggest that supply growth is at least sufficient to meet demand growth over the course of the next 18 months, a major departure from the long-term trend which portrays a constant struggle to maintain investment levels sufficient to ensure adequate supply. From a fundamentals perspective, this implies lower prices, unless of course, OPEC significantly curtails its output.

The second departure from the long-term trend is not so much the decline in OECD demand, which is heavily concentrated in Europe and accentuated by the weak economic outlook in that region, but in the regional balance of supply and demand in the OECD. OECD demand is expected to drop by 200,000b/d in 2013, according to the IEA, by 260,000b/d by the EIA, and by 100,000b/d by OPEC.

The fall in European demand is offset by smaller rises elsewhere. Japanese demand is seen as flat or falling, reverting to long-term trend as its nuclear capacity comes back on line.

However, with the exception of the IEA forecasts, the fall in European demand is seen as greater than the drop in the region's supply, implying less need for imports. In addition, US and Canadian supply growth outstrips demand growth by about 400,000-600,000b/d.

This is a reversal of the long-term expectation that the OECD will become more dependent on imported crude. In the US, this is the result of tight oil production, liquids associated with shale gas and biofuels. While in Europe, it reflects mainly the drop in demand as a result of low expectations for economic growth, but also a trend towards oil displacement and its more efficient use.

The third departure from the long-term picture is the dependence of non-OECD growth on the health of OECD economies. While China, and to a lesser extent India and the Middle East, remain the engines of demand growth in 2013, recent data on Chinese oil demand suggests demand growth is weakening, despite the continued development of the nation's strategic oil reserves.

China's apparent oil demand, which does not take into account changes in inventories, showed a rise of just 2.56 percent in the January-May period, year-on-year, up from 195. 42 million mt to 200.42 million mt. June data showed a drop of 1.9 percent year-on-year.

China's rate of GDP growth in the second quarter also shows clear signs of slowing, dropping to 7.6 percent from 8.1 percent in the first quarter. Some analysts have questioned the official figure, arguing that growth is in fact weaker than claimed. They argue that the slowdown is not just the result of lacklustre export markets, but a reflection of growing problems within the domestic economy, led by speculative bubbles, inflation and growing bad debts.

Long-term oil demand forecasts do expect the rate of Chinese GDP growth to slow in coming years, in comparison with the rapid growth of the last decade, but they also assume a shift in the balance from export-dependent growth to a stronger internal dynamic, a scenario put in doubt by current data.

Uncertainties

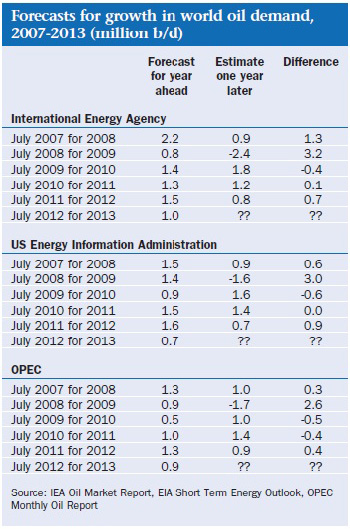

There are, of course, huge uncertainties in the forecasts. In the last five years, the average difference between the July forecast for the change in global oil demand for the year ahead and where the forecast was one year later--six months through the year being forecast--was 1.14 million b/d for the IEA, 1.02 million b/d for the EIA and 0.84 million b/d for OPEC.

These averages are large in part because none foresaw one year ahead the massive slump in demand in 2009 that resulted from the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

For 2009, the forecasts in July of the preceding year were around 3 million b/d out. In the short period considered, the EIA and IEA have tended to overestimate demand, while OPEC is regularly the most bearish, and this has generally proven the right viewpoint to take.

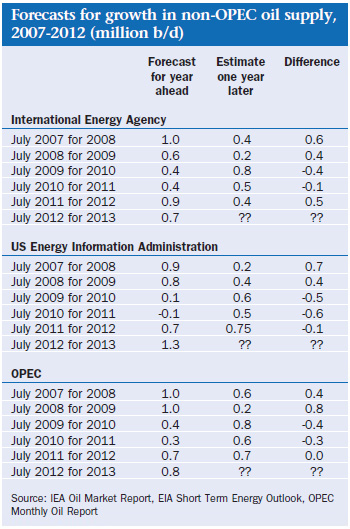

Similarly, the change in non-OPEC supply has been very difficult to predict. Between 2007 and 2012, the difference between year-ahead forecasts and July of the year predicted has been out by as much as 800,000 barrels too high and 600,000b/d too low. Such variability is enough in the current market to mean the difference between growth and contraction in non-OPEC's share of the market. As such the significance of these forecasts lies in their impact on expectations rather than any predictive power.

Aberration or paradigm shift?

Short-term trends at variance with the longer-term outlook do not necessarily mean that the longer-term outlook has to be rethought. There is a well-documented tendency in forecasting for the most recent events to gain greater significance than they actually merit. Equally, however, key turning points, in which long-term forecasts undergo significant change, are generally pinpointed retrospectively rather than at the time.

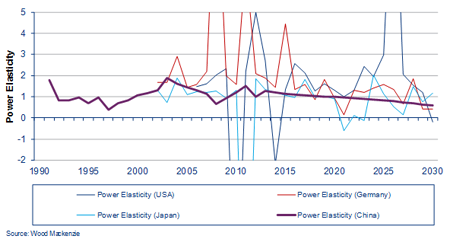

Yet the short-term trends can be placed in a longer-term context: The contraction in OECD demand embodies a level of permanent demand destruction that reflects not just high oil prices, but policies designed to reduce the oil intensity of economic activity. This trend may gather momentum and proliferate across the developing world, upsetting assumptions about the non-OECD's expected growth in oil demand.

The roles of technology and policy are critical in this area, while the experience of solar power and shale gas indicate that under the right regulatory conditions growth in disruptive technologies can be exponential.

Finally, there is the outlook for the world economy. There are two key weak points. First is that the Eurozone crisis proves protracted, with high levels of debt pushing Europe into a cycle of high debt and low growth from which it proves hard to escape. This would mean growth below the trend level to which most long-term forecasts revert.

Second are the uncertain limits to Chinese growth. Chinese GDP growth has surprised on the upside over the last decade. The process of urbanisation accompanied by rising incomes in such a populous country should mean that the country remains central to oil demand growth.

However, internal economic pressures combined with weaker export-orientated growth at the least puts on the radar screen the possibility that the Chinese juggernaut will run out of steam.

The short-term forecasts suggest a softer outlook for prices in the next 18 months, but the balance of supply and demand can be altered at a stroke by OPEC, while geopolitical concerns regarding Iran remain an ever present threat to oil market stability. As such, while oil price forecasts for 2012 have tumbled in recent months, they remain as much art as science. The more important aspect of the short-term outlook is whether it represents a turning point that challenges the longer-term assumptions on which current investments are being made.

BY : Ross McCracken, Platts Energy Economist