Since 1995, the electricity industry in Singapore has been privatised and progressively deregulated. The driving force in this journey has been the belief--consistent with standard economic principles--that a competitive energy market will be more efficient as profit-maximising producers strive to reduce production costs and compete for customers.

Any remaining monopoly power in the market can be controlled through proper design of the market structure as well as rules that prevent anti-competitive behaviours.

On the whole, retail competition has benefited consumers in Singapore. The drive for full retail competition in Singapore is taking place alongside the emergence of smart grid technologies. Both trends have the potential to advance energy efficiency and conservation in Singapore and to help consumers make better electricity consumption decisions.

This report looks at how behavioural economics can provide useful ideas for energy regulators in promoting competition in the electricity retail market. The central argument is that while full retail competition will give consumers more choice over their electricity retailers and plans, this alone is not sufficient to ensure good consumer outcomes.

By offering insights on how consumers decide when faced with complicated choices, in which the information needed is often not salient or timely, behavioural economics provides useful inputs to energy policymakers, particularly on how to structure choices in a way that improves individual consumption decisions and enhances overall energy efficiency.

Providing information to overcome the status quo bias

An important consideration when implementing full retail competition is to determine how consumers choose their retailers and pricing plans. One model is the "big bang" approach, which is to open up the entire customer market at one go for retail competition.

Since consumers may not actively exercise choice, this approach requires the authorities to assign default retailers and plans to consumers. Behavioural economics predicts that many consumers are then unlikely to switch out of the default plan for them, even if it is in their best interests to do so--an effect known as the status quo bias.

In their paper "Behavioural Science and Energy Policy", Allcott and Mullainathan (2010) provide possible reasons for this bias: Procrastination, the endowment effect (people's implicit preference for their existing plans), and the costs of acquiring information about alternative options.

Status quo bias contradicts the predictions of conventional economics which predicts that consumers will switch as long as switching is cheap and saves them money. It can result in markets with a low overall churn rate (i.e. the rate of consumers switching retailers), which in turn could undermine the efficiency of a fully competitive electricity market.

Behavioural economics suggests that participants would likely stay with their existing plan, due either to the status quo bias or to consumers' unfamiliarity and fears that they could be made worse off if they switched. To address this, the trial included a "recommended offer" package that was made available to all participants.

The system would calculate the least-cost option based on that particular household's consumption profile from the previous month and recommend the appropriate package to them. For example, the system would recommend Pricing Plan A to a household which consumes most of its electricity in the evenings. This feature was made possible by smart meters installed in the homes of the trial participants, which recorded household consumption in half-hourly intervals and enabled the system to determine the "recommended offer".

As a result of this feature, about 95 percent of the participants opted for either Pricing Plan A or B, instead of staying with the status quo plan. This suggests that providing a "recommended offer" option, made possible by smart metering technologies that identify the plan that is most suitable for the user, may be sufficient to overcome consumers' status quo bias.

Even consumers who may not be well-informed of the options available to them might switch if they are told that they would enjoy savings under a different plan.

Increasing energy efficiency through saliency and social norms

Promoting energy efficiency and energy conservation among consumers is another important policy objective of many governments.

While the power system has traditionally been built around a "supply follows demand" approach, where generation capacity is typically invested ahead of demand, studies have suggested that it is cheaper to invest in energy efficiency than to invest in energy generation, such as building a new power plant (Lovins 2007).

Standard economics suggests that to achieve higher levels of energy efficiency, energy prices will have to be raised (for instance, through an energy tax). Higher prices create a stronger incentive for consumers to reduce their usage, while signalling to energy companies to develop and implement energy efficiency solutions.

Conventional economics also assumes that individual consumers are rational beings who optimise their consumption regardless of how the information is presented. Behavioural economics suggests an alternative approach. It argues that presenting information that is salient to the choices and framing that information appropriately can go a long way in influencing consumers' behaviour.

In an experiment, Cialdini et al. (2008) studied the impact of different messages to encourage hotel guests to reuse their towels. Various messages such as "Save the Environment", "Preserve Resources for the Future", and "Partner with the Hotel to Save the Environment" were printed on cards which were visible to hotel guests.

The outcome of this study was that the card with the message "Join Your Fellow Citizens in Helping to Save the Environment", which provided the information that 75 percent of hotel guests reused their towels, increased towel reuse by the largest margin of 39.2 percent--a clear indication that appealing to social norms can make a stronger impacton consumers' behaviour.

Another barrier to energy conservation is that consumers find it difficult to know how much energy they are using at any point in time. This is exacerbated by the typical time lag of about a month between their actual consumption and their receipt of the monthly utility bills. This lag reduces the immediacy and saliency of the information, and weakens the motivation for consumers to change their habits.

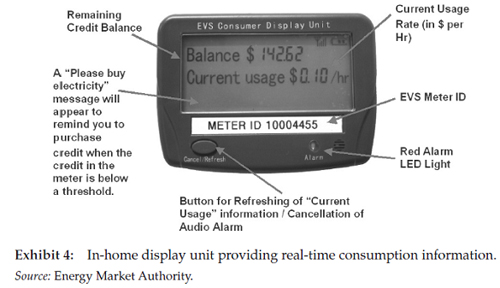

Technological advances such as smart meters make it possible to provide consumers with more information and control over their energy consumption patterns. The question of interest to energy regulators is whether making available real-time information enabled by these technologies (see Exhibit 4) can promote energy conservation and modify usage patterns to a degree significant enough to justify their large-scale deployment.

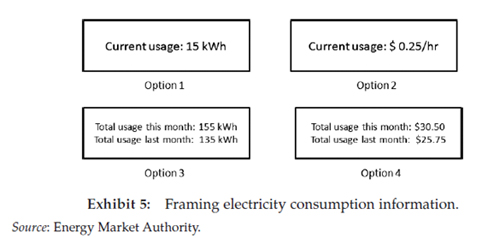

How might the information be presented in a way that impacts energy consumption levels"live" information of their electricity usage (Exhibit 5).

Behavioural economics suggests that showing consumers their usage in monetary terms (Options 2 and 4) will have a greater impact than showing them the units of electricity used (Options 1 and 3), as the former makes more intuitive sense. It also suggests that showing consumers their consumption level on a real-time basis (Option 2) may be more effective than showing them their cumulative usage over the month (Option 4), since the former provides current, rather than backward-looking information.

Another possibility is to make use of ambient displays which alert consumers of high levels of electricity consumption through changes in colours or light displays (Darby 2006). Martinez and Geltz (2005) described an experiment where electricity consumers were provided with a device called an "Energy Orb", a globe that changes its colour according to the time-of-use tariff in operation.

The study indicated that the flashing alert of higher tariffs resulted in higher overall savings and more load-shifting, strengthening the case for visual cues as long as they are cost-effective.

The key challenge then in designing any electricity information system is to identify the signals that are the most effective in inducing behavioural change, all the while bearing in mind the risk of "information overload". Psychologists have documented a reduced sense of individual efficacy when people are overwhelmed by the choices presented to them.

The key takeaway for regulators and utility companies is to calibrate the number of choices and the amount of information to provide consumers. They should also ensure that the choices presented to consumers are clear and easy to understand.

Singapore's Intelligent Energy System (IES) pilot

In Singapore, full retail competition is still a work in progress. The eventual aim is to give consumers greater say over their electricity retailers and pricing plans and to harness the full range of available technologies to improve Singapore's energy efficiency.

Conclusion

While standard economics still underpins the formulation of energy policies in Singapore, behavioural economics provides additional insights in explaining consumer behaviours and in formulating energy policies. The introduction of full retail competition will increase choice for consumers but simply expanding the range of options may not result in good decisions by consumers.

The technological advancements that the IES offers will allow utilities companies and energy regulators to provide salient and timely information to consumers. By combining the insights of behavioural economics with these new technology solutions, policymakers can devise creative measures that help consumers save money and promote energy efficiency

The views expressed here are the authors and are not those of the Energy Market Authority or Civil Service College. This extract is published with permission from the forthcoming book "Behavioural Economics and Policy Design: Examples from Singapore" (edited by Mr Donald Low and scheduled for release in October 2011), and is a copyright of the Civil Service College, Singapore.

BY: Eugene Toh and and Vivienne Low